New Potential for Improved Conservation Around the W-Arly-Pendjari Complex in West Africa

When the privately-owned African Parks Network (APN) assumed management responsibility for Pendjari National Park, Benin in mid-2017, it created a new reality for conservation management in the region, including collaborative opportunities for other organisations operating locally too.

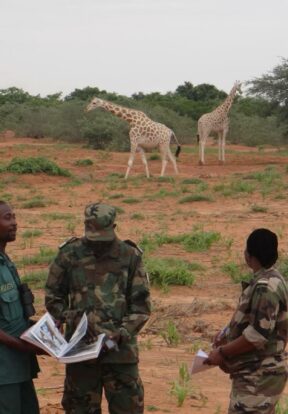

Pendjari is important in its own right. But it is also a key part of the 1-million-hectare W-Arly-Pendjari complex spanning Benin, Burkina-Faso and Niger. Together, WAP is one of West Africa’s most important biodiversity safe-havens. The landscape also includes Arly National Park in Burkina-Faso and the transboundary W-Park, named after a W-shaped series of bends in the Mekrou river. For wildlife, the WAP complex is a key remaining regional stronghold for threatened species including Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), West African Giraffes (Giraffa camelopardalis peralta), African wild Dogs (Lycaon pictus), Elephants (Loxodonta africana), Lions (Panthera leo) and Leopards (Panthera pardus), says Muyang.

The health of the WAP complex has and continues to be threatened by poaching, habitat loss due to encroachment and poorly coordinated governance by different park authorities, however. Better park management will support other conservation outcomes for WAP, something hopefully the APN model will bring. Given its relatively large surface area, there is potential for species numbers to bounce back in the long term if these inter-related issues can be addressed in a synchronised approach. With three different government authorities managing the area, there is significant scope to improve coordination and management effectiveness too. In the past, for example, species inventories were completed using differing methods, making it difficult to accurately assess species populations or trends in these numbers over time.

Pendjari is home also to at least ten tourist camps and hunting concessions. If well managed, increased visitor numbers to the complex could generate income for local community members and the protected area authorities involved. What is more, its location in the dry Sahel zone of West Africa gives the complex an absolute advantage over the long-term in that habitat encroachment can be controlled in this area relatively easily, explains Muyang. Yet human animal conflict in terms of poaching and transhumance – a seasonal movement of livestock between summer and winter pastures- is current. Various locally-focused socio-economic studies confirm it is a key driver for poaching and killing of wildlife. About 10,000 people reside in the buffer zone of the park complex performing agricultural activities including transhumance. While it affects just 5% of the total area such activity causes conflict between wildlife and people, says Muyang undermining other livelihood opportunities.

APN working with local government together with projects supported by IUCN Save Our Species can make a change. Muyang elaborates, “if communities had alternative sources of income and protein, poaching rates of antelopes would likely decrease in the area, in turn, increasing the prey base for carnivores and so boosting their survival rates”. Historically the APN business model had been to assume responsibility for park management in protected areas. Only in this way remaining in partnership with a national government, could it guarantee results. This situation can then facilitate coordination with actions performed in and around Pendjari. And with APN also preparing to assume management of Benin’s portion of the W-Park the prospect of additional resources, support and capacity is another positive development.

Meanwhile to eliminate duplication of effort and optimise synergies, some NGOs operating in the region were encouraged to coordinate with each other and with other programmes funded by the European Commission across this complex landscape. These collaborations were established especially on key activities related to species monitoring and anti-poaching efforts. And while the trans-boundary dimension of the WAP complex made synchronized intervention inherently challenging to begin with the new management system could help build the capacity and management effectiveness in the WAP complex, as APN has done elsewhere.

Planned activities for IUCN Save Our Species funding include performing bio-monitoring of wildlife species to produce reliable data on their status and distribution in the WAP. Projects would also help put in place structures to develop the socio-economic activities of some of the neighbouring communities as well as mechanisms to reduce human wildlife conflicts and the bush-meat supply chain. Similarly, they aim to improve coordination efforts in park management while training park authorities on law enforcement actions. Meanwhile, one NGO operating in the area, the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) has planned to support the government of Niger in their first-ever translocation exercise for the Endangered West African Giraffe establishing a second major population which will increase the animals’ habitat range and reduce risk of poaching and disease affecting this species.

Achieving project objectives means adaptive management. In addition to the advantages of increased resources supporting conservation in the region these developments with APN present opportunities to realise specific activities such as anti-poaching patrols, species monitoring and the planned Giraffe translocation work according to standardised and best practices.

A coordination meeting recently held in Niamey, Niger helped identify gaps and ways of harmonising intervention actions to ensure efficient implementation and use of available funds. It is an important step on a long-journey toward making the W-Arly-Pendjari complex West Africa’s most important biodiversity safe-haven.