SOS African Wildlife: Championing Community-Led Conservation

This article is published as part of the 30th edition of ‘A Call from the Wild’, IUCN’s quarterly Species Conservation Action newsletter. This edition focuses on indigenous communities and their importance to conservation.

Indeed the lives of 21st Century Africans are changing rapidly, even in rural landscapes where traditional ways of life still prevail. Successful actions to conserve Africa’s wild species, including its iconic carnivores, include those that tap into indigenous traditional knowledge and cultural values to develop practical solutions that foster harmony between communities and wildlife.

For example, work with different indigenous communities, including the Maasai, the Barabaig, the Toka, the Tonga, the Lozi and the Tokaleya across multiple ecosystems in Tanzania and Zambia is achieving this.

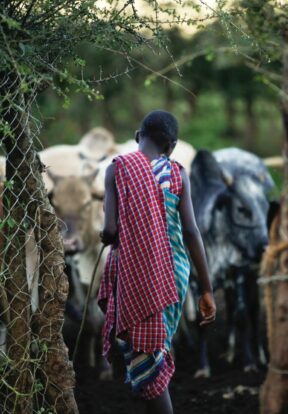

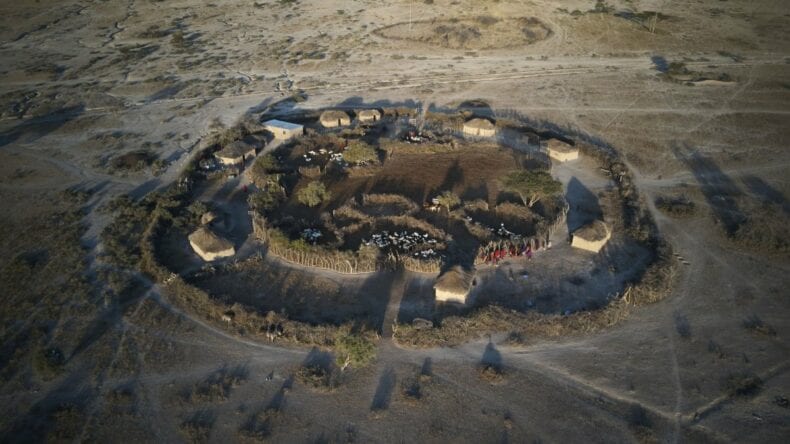

In northern Tanzania, the Maasai people, who once killed large carnivores, are now helping to save them. As pastoralists, communities in this region historically took revenge on lions for attacking valuable livestock. Lions were able to penetrate protective corrals made from the dried thorny of Acacia trees. Not only were these corrals ineffective against predation, but they also contributed to deforestation.

In 2008, Tanzania People & Wildlife (TPW) worked closely with a local Maasai community to develop the Living Walls concept, which is based on the original corral design. By replacing the dead thorny branches with living Commiphora trees and connecting them with chain-link fencing to fill any gaps and fortify the overall structure, together they achieved a 99% success rate in preventing livestock attacks. In fact, over the past 11 years, not a single lion has been killed at a homestead with a Living Wall. As a result, TPW reports that lion populations in areas with high densities of Living Walls are showing signs of recovery. Furthermore, the 140,000 trees planted so far in the landscape arecontributing to the regeneration and preservation of vital wildlife habitats.

However, Living Walls are not just benefitting wildlife. Families who own Living Walls enjoy more productive, peaceful, and prosperous lives. Many even have a more positive attitude about living with wildlife now that human-wildlife conflict levels have reduced.

And for TPW, lessons learned from the success of the Living Walls project have transformed their approach to project development: today, co-creation has become the organisation’s guiding principle.

In southern Tanzania, in the Ruaha landscape, the Barabaig community, who share a common heritage with the Maasai, is also working to save the carnivores they used to kill. When the Ruaha Carnivore Project (RCP) launched their community conservation work in the area, they counted above average carnivore killings on village land and the Barabaig seemed to play a key role. In Barabaig tradition, killing a lion was not only a rite of passage but also a way to get ahead in life. The young man to spear a lion first earned gifts of cattle but also the attention of local young women.

However, the Barabaig being relatively closed to outside influence meant initial engagement efforts proved fruitless. That was until some Barabaig warriors noticed the solar panels at the conservationist’s camp and came asking to recharge their mobile telephones. And so a rapport began, allowing RCP to develop a discourse about carnivore conservation and eventually to co-create appropriate conservation programmes, such as the warrior engagement programme, in partnership with the community. The programme works with young warriors to track lions and warn the community of their presence, while also helping safeguard livestock and to prevent others from killing lions. Transformed from hunters to “Lion Defenders”, warriors can now use conservation to credibly maintain their traditional role as community protectors, and still get ahead in life.

In Zambia, development is underway on a proposed new community conservancy model, made possible due to the support and guidance of the traditional leaders from four chiefdoms, says Dr Rosemary Groom. A key tract of land that will help connect the Kafue National Park with the rest of the Kavango–Zambezi (KAZA) Transfrontier Conservation Area remains under traditional ownership, headed by multiple chiefs. The carnivores of Kafue are under pressure from poaching and issues of disconnection and isolation from other wildlife areas. Restoring connectivity is hugely important for wildlife, but also for the locals who will benefit in the long term from livelihood development based on a wildlife economy. Land tenure in the region, however, is complex and disputes among the chiefdoms over boundaries are deep rooted and complicated.

Given these considerations, the ‘Keeping Kafue in KAZA’ project team felt a community conservancy model would be the best approach: allowing local communities to conserve their land and natural resources in a way fully reliant on the people themselves.

Working with the communities across the chiefdoms through the chiefs and their councils of elders, the key was to present the project as a united concept. This afforded chiefs and communities alike a sense of shared ownership with focus on a common goal. Putting aside any disputes over land ownership, they came together, naming the project ‘Inyasemu’ – a construct of the four chiefdom or chief names. Six months in, momentum is picking up with the chiefs touring all four chiefdoms to jointly present the project to their communities. Furthermore, community consultations are also being held to gather people’s thoughts and suggestions for the way the conservancy could best operate.

These examples highlight the ethos of the SOS African Wildlife initiative. The initiative is working to halt the decline of five carnivore species – Lion, Leopard, Cheetah, African Wild Dog and Ethiopian Wolf – and many of their prey species by supporting projects that focus on implementing solutions that empower communities to participate and engage in conservation, as well as creating innovative livelihood solutions.

The SOS African Wildlife initiative is funded by the European Commission’s Directorate General for International Cooperation and Development (DG Devco) through its B4Life initiative.