The Importance of Gender Equality in Conservation: Interview

But this is now changing, and for a very good reason: Considering gender when planning policy helps to ensure that women benefit from the conservation action as much as men.

In many countries, both women and men depend on protected areas for a living, but nevertheless have differentiated roles, access and experiences. For example, women and men may play different roles within their community, having different traditional responsibilities within the economic life of their family, or have unequal access to natural ecosystems and their uses. These differences often take the form of gender inequality: women often have less access to natural resources than men and are less involved in decisions over the conservation and communal management of protected areas. Unfortunately, these kinds of gender inequality tend to restrict the economic independence of women, keeping them in poverty, and undermining the sustainable use and management of protected areas. But gender-responsive policy can mitigate these differences, increasing the benefits of the conservation action for women and men alike.

For example, IUCN is currently working with the Government of Malawi to plan the restoration of 45,000 km2 of forest landscape, part of the 2011 Bonn Challenge, an international effort to restore 1.5 million km2 of the world’s degraded and deforested lands. In the planning phase, IUCN staff took care to interview Malawian women and men, asking them about their priorities. The answers were revealing: while men mostly urged the planting of “cash crops” – that is, tree species that yield charcoal and timber – women tended to ask for medicinal and fruit trees. By planting a mix of female- and male-preferred species, conservationists could thus simultaneously improve the economic security, health, and nutrition of the local people.

Since 1998, IUCN’s efforts to make sure that gender equality is always taken into account in its work have been spearheaded by its Global Gender Office (GGO), based in IUCN’s Washington D.C. office. The GGO’s remit is to equip IUCN Members, offices, and commissions with policy, technical support and innovation tools for gender-responsive conservation-policy.

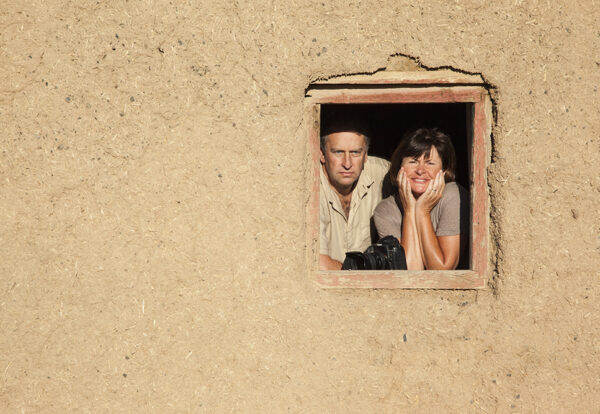

Here, we interview Jackie Siles, Senior Gender Programme Manager and Jamie Wen-Besson, Communications Officer for IUCN’s GGO.

Jackie, Jamie, why is gender equality in conservation so important?

Jamie:

Hello, thank you for interviewing us and we’re so glad you ask! Simply put, effective conservation is not possible without the voices, knowledge, solutions and contributions of women, who make up half of every population. Their adaptive capabilities make them an important resource in addressing climate and environmental challenges. Economists estimate that women make up 80% of household spending decisions and they account for 43% of the global agricultural workforce, with the FAO estimating that equal access for women to extension services and credit could increase farm yields by 20-30%. However, inequality is a barrier to this potential: women currently have access to 5% of extension services and 1% of agricultural credit while 90% of 143 economies have at least one law that restricts women’s economic equality. It is also important to recall that global development agendas recognise that gender equality and women’s empowerment are matters of fundamental human rights and social justice.

What does a typical day in your work at the Global Gender Office look like? What aspect of your job do you like the most?

Jackie:

At the Global Gender Office, there are no two days that are alike. In one moment, I am travelling to various regions of the world to provide technical support and advice to Member countries, partners, local communities or environmental and climate negotiators. Meanwhile, some of my colleagues conduct research, data analysis and work towards building an evidence and data-based approach to gender, conservation and the environment. For all of us, the best parts of our job are the people and communities we work with. We have a mission to serve their needs and to help contribute solutions that work for them, whether it means conducting advocacy, engaging governments, working on the ground, collaborating with donors and partners, building knowledge or doing policywork.

A key tool in early-stage policy-planning is the Gender Analysis. Can you tell us how this works?

Jackie:

A gender analysis is the fundamental first step in integrating gender throughout policy, programme and project design alike. A gender analysis seeks to ask a wide range of questions to ask local communities that are designed to provide insight on gender roles, responsibilities and gaps that exist. The answers not only illuminate possible risks and opportunities associated with interventions but also help establish baseline indicators and data against which we hope to eventually measure progress. While different institutions and companies conduct gender analyses differently, they should all seek to prioritise action based on learning and understanding.

What further tools and strategies does the Global Gender Office have to ensure that women are fully represented at all levels in the IUCN’s actions, for example as beneficiaries, decision-makers, and conservationists?

Jamie:

The Global Gender Office has numerous strategic tools and approaches towards seeking women’s active and meaningful participation at all levels. At IUCN, the team supports a network of Gender Focal Points across IUCN’s global programmes and regions to assist active engagement across the Secretariat on gender issues. The team is also involved in working with UNDP and IUCN colleagues in developing a gender certification programme that recognises the gender-responsive work of IUCN offices that is designed to promote best-practice sharing. At the decision-making level, the team works towards providing data and evidence that uncovers the reality of both gender gaps and advancements and also assists policy design and advocacy. Across conservation, the team works closely with IUCN colleagues and donor partners on the ground to ensure programmes and projects implement interventions that improve conservation outcomes through the advancement of gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Additionally, a very important way we advance our work is through the development of climate change Gender Action Plans (ccGAPs) wherein the team works with national governments in cataloguing legal frameworks on gender and the environment, assessing gender in each environmental priority sector and what innovative opportunities exist to promote women’s empowerment while improving the environment. In Egypt, this has led to the creation of Nile water taxis run by women for women to address their safety in public spaces while providing more environmentally friendly ways to get around. In Peru, the ccGAP has led to the creation of gender focal points in the Ministry of Energy, thereby systematising commitment towards gender equality.

But not all of these ccGAPs are at the national level, they’re sometimes sub-national. In fact, the team recently worked with UNDP Mexico in developing a landmark ccGAP, the first for a protected area managed by indigenous people. IUCN and partners worked closely with the Comca’ac people to highlight the unique experiences, knowledge, priorities and needs of indigenous women and men of Sonora to diversify livelihoods to strengthen resilience.

Does the Global Gender Office encounter much resistance from IUCN specialists and/or stakeholders in the field in its mission to ensure gender equality in all conservation actions?

Jackie:

We are fortunate to work in an organisation that was one of the first to embrace gender as an essential part of the global development, conservation and environmental agendas. We have found that the most resistance was really about a lack of knowledge on the critical role women play in environmental conservation. Under the leadership of Lorena Aguilar, who is now Vice Chancellor for Foreign Affairs in my home country of Costa Rica, we worked positively and proactively by addressing these knowledge gaps through advocacy, using trainings, presentations, and most importantly, by proving the case through on the ground work.

How do the women in developing countries with more patriarchal traditions typically react to being explicitly involved in decision-making about conservation policy?

Jamie:

This is a common question. In my observations of my colleagues, their work and their engagements, I have come to learn that these feelings and thoughts about ‘patriarchal traditions’ or ‘culture’ are more about ensuring people have information about how women’s empowerment and the advancement of gender equality is about lifting up entire families, communities and environments together along with women. In some places, we’ve worked with women who were initially told they could not take part in entrepreneurial opportunities by husbands. By addressing concerns, explaining economic benefits and building in considerations regarding non-productive roles, we’ve seen these men not only give their blessing but also become the proud spouses of entrepreneurial women. As a good friend would always say, if everyone is willing to embrace cell phones, they can embrace other changes too.

Can you give us an example of a success story: a conservation action with full gender equality in planning and execution?

Jackie:

In 2016, the IUCN GGO provided technical support to more than 30 organisations working on conservation in the Andean Amazon Region to mainstream gender into their work. One of these organisations was the Sinchi Amazonic Institute of Scientific Research, a non-profit research institute of the Government of Colombia charged with carrying out scientific investigations relating to the Amazon Region of Colombia to better understand the region as well as how to protect it. We worked closely with the Institute on a gender analysis for a bio-prospective study in three departments of the region. By including gender issues in their research methodology and analysis, the Institute was able to report on 45 new species which had not been previously identified in the region as local women and men had differentiated knowledge of species. The results of this process thereby highlighted the important role and knowledge Amazon women can have in the development of policies and initiatives related to forest management and food security.

Jamie and Jackie, many thanks for your answers! We from IUCN Save Our Species team wish you and the rest of the GGO every success in your important work.